Lixus

Webmaster

Bibliographie

ARMSTRONG, Albert, 1931, « Rhodesian archaeological expedition (1929) », Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 61, p. 239-276.

ARNOLD, G., JONES, Neville, 1919, « Notes on the Bushman cave at Bambata, Matopos. », Transactions of the Rhodesian Scientific Association, 17 (1), p. 5-19.

BOURDIER, Camille, 2019, « Peintures rupestres et environnements culturels des Matobo, Zimbabwe », in G. PORRAZ, A. VAL, T. VERNET-HABASQUE, Préhistoire et hommes modernes, Lesedi Field Notes, 21, p. 25-29, https://issuu.com/french-institute/docs/2019-lesedi21-fr

BOURDIER, Camille, DUDOGNON, Carole, FROUIN Millena, NHAMO, Ancila, RUNGANGA Todini, & TOURON, Stéphanie, 2020, « Approche interdisciplinaire de la paroi ornée: Pomongwe Cave et le programme MATOBART », in L. JOBARD, C. DUDOGNON, C. BOURDIER, The Rock Art of the Hunter-Gatherers of Southern Africa, Lesedi Field Notes, 23, p. 13-18, https://issuu.com/french-institute/docs/2020-lesedi23/s/11397952

BURKITT, Miles Crawford, 1928, South Africa’s past in stone and paint, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

BURRETT, Robert S., FITZPATRICK, Moira, DUPRÉE, Julia, 2016, The Matobo Hills: Zimbabwe's sacred landscape (First ed.). Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

COOKE, Cran, 1963a, “Report on excavations at Pomongwe and Tshangula caves, Matopo hills, southern Rhodesia”, The South African Archaeological Bulletin, 18 (71), p. 73-151.

COOKE, Cran, 1963b, « The painting sequence in the rock art of southern Rhodesia », South African Archaeological Bulletin, 18 (72), p. 172-175.

COOKE, Cran, ROBINSON, K. R., 1954, “Excavations at Amadzimba Cave, Matopo Hills, Southern Rhodesia”, Occasional Papers of the National Museum of Southern Rhodesia, 2 (19), p. 699-728.

DUDOGNON, Carole, FROUIN, Millena, TOURON, Stéphanie, NHAMO, Anicla, MACHIWENYIKA, Kelvin, PORRAZ, Guillaume, RUNGANGA, Todini, BOURDIER, Camille, 2021, « Recherche, conservation et valorisation d’un patrimoine mondial : des défis multiples dans les Matobo, Zimbabwe », in B. FAVEL, C. GAULTIER-KURHAN, G. HEIMLICH, Art rupestre et patrimoine mondial en Afrique subsaharienne, Paris, Hémisphères, Nouvelles éditions Maisonneuve & Larose, p. 67-90.

GARLAKE, Peter, 1987, The painted caves, Harare, Modus publications.

GARLAKE, Peter, 1995, The Hunters’ Vision: The pre-histone Art of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe publishing house.

HUBBARD, Paul, 2018, “The Rock Art of the Matobo Hills World Heritage Area, Zimbabwe: Management and Use, c 1800 to 2016”, Conservation and management of archeological sites, 20(2), p. 76–88.

HUFFMAN, Thomas, 2007, Handbook to the Iron Age, Durban, University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

JOBARD, Léa, 2020, “Matobo Rock Art in its Landscape”, in L. JOBARD, C. DUDOGNON, C. BOURDIER, The Rock Art of the Hunter-Gatherers of Southern Africa, Lesedi Field Notes, 23, p. 36-41, https://issuu.com/french-institute/docs/2020-lesedi23/s/11397956

JONES, Neville, 1926, The Stone Age of Rhodesia, London, Oxford University Press.

JONES, Neville, 1933, “Excavations at Nswatugi and Madiliyangwa, and notes on new sites located and examined in the Matopo Hills, Southern Rhodesia, 1932”, Occasional Papers of the National Museum of Southern Rhodesia, 1 (2), p. 1-35.

KUMIRAI, Albert, MSIMANGA, Audrey, MUNYIKWA, Darlington, CHIDAVAENZI, Robstein, MURINGANIZA, SVINURAYI, Joseph, 2003, Nomination dossier for the proposed Matobo Hills World Heritage Area, https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/306/documents/

LARSSON, Lars, 2001, “The Middle Stone Age of Northern Zimbabwe in a Southern African Perspective”, Lund Archaeological Review, 6, p. 61-84.

MAKUVAZA, Simon, 2014, “From colonialism to independence: The management of cultural heritage in Zimbabwe”, in C. SMITH, Encyclopedia of global archaeology, New York, Springer, p. 7965–7973.

MGUNI, Siyaka, 2015, Termites of the gods: San cosmology in Southern African rock art, Johannesburg, Wits University Press.

NHAMO, Ancila, 2013, « Of borrowed concepts and regional variations: a critique of rock art interpretative frameworks with specific reference to Zimbabwe », in M. MANYANGA, S. KATSAMUDANGA, Zimbabwean Archaeology in the Post-Independence era, Harare, Sape Books, p. 61-74.

NHAMO, Ancila, BOURDIER, Camille, 2019, “Matobo Rock Art”, in C. SMITH, Encyclopaedia of Global Archaeology, New-York, Springer, doi. Org / 10.1007 / 978-3-319-51726-1_3252-1.

PORRAZ, Guillaume, CHIWARA, Precious, HAALAND, Magnus, MNKANDLA, Thubelihle, MACHIWENYIKA, Kelvin, RUNGANGA, Todini, TRIBOLO, Chantal, VAL, Aurore, BOURDIER, Camille, 2020, “Les sous-sols de l’art rupestre à l’abri Pomongwe”, in L. JOBARD, C. DUDOGNON, C. BOURDIER, The Rock Art of the Hunter-Gatherers of Southern Africa, Lesedi Field Notes, 23, p. 19-22, https://issuu.com/french-institute/docs/2020-lesedi23/s/11397951

PORRAZ, Guillaume, NHAMO, Ancila, BOURDIER, Camille, to be published, “Pomongwe cave, Zimbabwe”, in A. BEYIN, D.K. WRIGHT, J. WILKINS, D.I. OLSZEWSKI, Handbook of Pleistocene Archaeology of Africa, Cham, Springer.

RANGER, Terence, 1999, Voices from the Rocks Nature, Culture, and History in the Matopos Hills of Zimbabwe, Indiana University Press, 305 p.

SMITH, C.G., 1968, Some aspects of the Geology of the Matopos, Unpublished Honours thesis, University of Rhodesia, Geology Department.

WALKER, Nicholas, 1987, « The dating of Zimbabwean Rock art », Rock Art Research, 4 (2), p. 137-148.

WALKER, Nicholas, 1995, Late Pleistocene and Holocene hunter-gatherers of the Matopos, Uppsala, Studies in African Archaeology 10.

WALKER, Nicholas, 1996, The painted hills, Gweru, Mambo Press.

WALKER, Nicholas, 1998, The Late Stone Age. Ditswa Mmung, The Archaeology of Botswana, Gaborone, Pula Press and Botswana Society.

WALKER, Nicholas, THORP, Caroline, 1997, « Stone Age Archaeology in Zimbabwe », in G. PWITI, Caves, monuments and texts: Zimbabwean Archaeology today, Uppsala, Uppsala University, p. 9-32.

Recent and On-Going Researches at the Matobo Hills

Thanks to a long history of research, and exceptional archaeological records, Matobo is one of the premier places for Stone Age research in southern Africa. Still, it is lagging behind other regions due to the absence of absolute chronology, detailed technological analysis, and geoarchaeological studies. Dating and chronological sequencing of the rock art, in particular, have remained key outstanding issues, in Matobo as more broadly in southern Africa (Nhamo and Bourdier, 2019; Porraz et al., to be published).

Since 2017 the interdisciplinary research program MATOBART (coordinated by Bourdier, Machiwenyika, Nhamo, Porraz) is reinvestigating the Matobo Hills with the ambition to revise and precise the Stone Age cultural dynamics, combining rock art and the other spheres of material culture (Bourdier, 2019). Laureate of the Institut Universitaire de France and the French Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, and supported by the Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires Étrangères, it associates French and Zimbabwean institutions in Archaeological Research and Heritage – Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, CNRS, University of Zimbabwe, National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe, Ministère de la Culture – together with other scientific partners from Germany, Norway, and South Africa.

MATOBART tackles two central issues in rock art studies: age and conditions of beginning, and change and continuity through time. It aims: 1) To build up a refined rock art stylistic sequence through techno-stylistic analysis; 2) to provide new chronological milestones, mostly by crossing rock art with ground archaeology; 3) to integrate this chrono-stylistic sequence in an updated chrono-cultural sequence, comprising the re-evaluation of the equipment, production and the diet strategies. It is based on new cross-investigations of the rock paintings and the archaeological sequences of two sites: Pomongwe Cave on which research has focused so far, and Bambata Cave (Bourdier et al., 2020; Porraz et al., 2020). It combines field missions (rock art tracings, excavations), the re-examination of collections from previous excavations (painted spalls, pigments, painting equipment, lithics, bone industry, fauna) stored at the Zimbabwe Museum of Human Sciences in Harare, and new dating.

Rock art recording comes with the taphonomic study of the walls in order to distinguish paint remains from various coloured alteration deposits (Bourdier et al., 2020). This includes physico-chemical analysis of coloured micro-samples in laboratory. At Pomongwe Cave, the identification of several alteration processes has led to sanitary recommendations which would hopefully enhance the preservation of the paintings. To correlate the rock paintings with the archaeological layers, rock art recording focused on two sections, above former Cooke’s Trench I and Walker’s Trench V (Cooke, 1963a ; Walker, 1995). Dozens of unpublished motifs have been identified, including animals, humans such as a dancing scene, and two formlings (Dudognon et al., 2021). Two red paint recipes have been characterized – one ochre-based, the other hematite-based – either on the walls and on the spalls from Walker’s collections. But relating the spalls to their original assemblage remains challenging due to the rich accumulation of successive painted assemblages through time.

Trench I and Trench V were re-opened in 2018 to check the previously defined archeo-stratigraphic sequences, and to collect samples for geomorphological and paleoenvironmental reconstructions, and dating (Porraz et al., to be published). In Trench I, preliminary observations confirm Cooke’s main observations with an upper “LSA” sequence finely stratified, and a lower “ESA and MSA” more coarsely stratified with occasionally white ash-like features. In line with Walker’s descriptions, Trench V profiles showed a relatively horizontal stratigraphy with alternating combustion events and rich concentrations of organic material.

Studies are on-going. Recently the issue of Matobo LSA cultural dynamics has been broadened to the rock art landscapes (Jobard, 2020). Indeed MATOBART aims to impulse a long-lasting scientific collaboration between France and Zimbabwe on Stone Age archaeology in which academic and professional training is a crucial dimension. Excavations and rock art tracings act as training fields, rock art and material studies feed Masters and Doctoral researches in several universities.

(Camille Bourdier, Ancila Nhamo, décembre 2022)

The History of Research at the Matobo Hills

Matobo has a long history of archaeological research, since the beginning of the 20th century when the first European archaeologists begun to work in the region, and especially the rock art (N. Jones, M.C. Burkitt, L.A. Armstrong, C. Cooke). In other regions, traditional laws within local communities protected heritage sites, including rock art, for centuries (Makuvaza, 2014). Such a system must have existed in Matobo as well, which would explains the high number and exceptional preservation of the rock art sites at present (Ranger, 1999; Hubbard, 2018).

Until the 1980s, archaeological research was driven by the building of the regional Stone Age chrono-cultural sequence and rock art chrono-stylistic sequence. In such purpose the two first generations of prehistorians made attempts to correlate ground occupations and rock paintings. Several rock art sites were then excavated from the first half of the 20th century, notably Bambata (Arnold and Jones, 1919; Armstrong, 1931), Nswatugi (Jones, 1926, 1933), Amadzimba (Cooke and Robinson, 1954), Pomongwe and Tshangula (Cooke, 1963a). In the 1970s, a few sites were re-investigated by Nick Walker who also excavated a handful of new ones with a special focus on the Later Stone Age (LSA) sequence of occupation, from the Late Pleistocene to the Late Holocene (Walker, 1995). Apart from the redefinition of the chrono-cultural sequence, he specifically addressed the subsistence strategies, and adopted a paleo-social perspective with a multi-proxies approach (ecofacts, artefacts, sites distribution and features, rock art). In relation to climatic and environmental factors, he stated a model of socio-cultural dynamics in the longue durée, including elements of demography, settlement pattern, and social structuring.

With deep stratigraphic sequences, and extremely good organic preservation, the Matoban sites have proven to be key for the Stone Age cultural sequence of the whole southern Africa, from the Earlier Stone Age (Bambata, Pomongwe) in the Mid-Pleistocene up to the end of the LSA (Walker and Thorp, 1997). Amongst them, Bambata and Tshangula remain preeminent for the transition from MSA (Middle Stone Age) to the LSA regarding the issue of the cultural dynamics between these two phases (filiation vs break – Larsson, 2001; Walker, 1998). In Bambata again, the presence of pottery remains in the most recent occupations attributed to foragers’ populations put to question the effective influence of the first pastoral populations’ arrival (cultural borrowing vs local autonomous invention – Walker, 1995; Huffman, 2007).

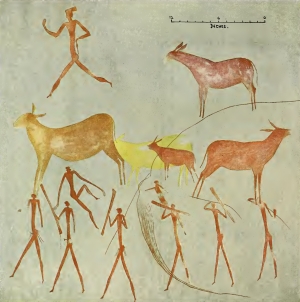

In parallel, a regional chrono-stylistic sequence of rock art was built by C. Cooke, with six styles: 4 attributed to the LSA foragers, and 2 to the Iron Age farmers (Cooke, 1963b). The LSA rock art sequence is based on a linear progressive complexification of techniques and forms, from plain monochromes to differentiated outlines and infills, fine outline drawings, and finally polychromes. This stylistic sequence has been strongly criticized for lack of objectivity and consistency in the use of analytical attributes. Walker complemented it with some radiocarbon dates obtained from the archaeological layers with material relating to the paintings (Walker, 1995, 1996). He assumed a beginning around 13.000-12.000 BP at Pomongwe and Cave of Bees which would make Matobo one of the oldest rock art testimonies, back to the Late Pleistocene (Nhamo and Bourdier, 2019).

Since the 1980s, archaeological research in Matobo has drastically reduced and focused on rock art only, with an emphasis on the meanings. Based on the exceptional ethnographic documentation from recent San populations in South Africa, this iconography was mainly considered as the expression of foragers’ spirituality – magical potencies embodied in animals, beings from the spiritual world, mythical characters – and ritual activities (Garlake, 1987; Mguni, 2015). For some scholars, it addresses a wider range of social symbolism: Gender, affiliations, and social networks identification (Garlake, 1995; Walker, 1995; Nhamo, 2013). Still none of these interpretative theories can explain all the motifs and compositions found in Matobo rock art so far.

(Camille Bourdier, Ancila Nhamo, décembre 2022)

The Matobo Hills in their Landscape

Matobo is derived from a term that means “bare stones” in the local Kalanga language. The name was popularised by King Mzilikazi, who led a migrating Ndebele group that settled in the area around 1832 (Burrett et al., 2016). The colonial settlers bastardized it into a number of variations such as Matopo, Matopo Hills or Matopos.

Located in south-western Zimbabwe, the Matobo UNESCO World Heritage Landscape forms the southwest margin to the Zimbabwean granitic shield. It lies at an altitude between c. 1200 and 1500 meters above sea level, at the border of the lowveld biome that makes the Limpopo-Shashe-Confluence-Area, the area of the three frontiers between South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe. Topographically, the Matobo comprises a series of hills that are generally separated by near-parallel N.N.W.-S.S.E. valleys where the rivers have exploited natural joints (Walker, 2012). The hills are mostly granite with a few intrusions of quartz, augen gneisses, older Archaean granites, grandiosities and dolerite veins (Smith, 1968). The Matobo batholith, brownish grey in colour, consists of medium-sized grains and is dated to around 2.6 billion years. It extends to cover about 2.050 km2 of World Heritage landscape and some surrounding areas (Kumirai et al., 2013). The granite weathers into various shapes and sizes which created a wide variety of rock formations: Large “whaleback” boulders, balancing rocks (“kopje”), cliffs (Smith, 1968). Concave spalling and related weathering processes often result in large rock shelters and rock overhangs which have provided a home to humanity as well as surfaces for paintings for thousands of years.

The Matobo lies in the Zambezian savannah biome, in a general semi-arid environment. Thanks to the altitude, the average annual temperatures seldom exceed 35 degrees Celsius. The climate follows a summer rainfall system, with increased precipitation during the summer months between November and February. Some perennial streams – Maleme, Mpopoma, Thuli – either run through or emerge from it before they eventually join the Shashe River and Limpopo River some 150 km further south. However, there are several more seasonal streams that bisect the landscape. Soils are mostly coarse and sandy, with few clay and organic soil pockets. Nevertheless, the variety of land features and their different response to climatic conditions offer a mosaic of habitats over short distances. The vegetation is characterized by forest vegetation mixed with shrub and grassland, typical of Highveld biomes. Hence the Matobo natural heritage includes a high botanic diversity of over 200 species of tree and over 100 grass species (Burret et al., 2016).

With this high diversity of vegetation and landforms comes a wide variety of fauna: 88 mammals, mainly small to large herbivores with 25 species of rodents, 13 of antelopes, 2 of rhino (including the almost extinct white rhino), and domesticated grazing species such as cows and goats, together with about 175 bird species and 16 fish species (Burrett et al., 2016). An exceptional density of predators goes with them (leopard, baboon, 39 snake species like python and black mamba, raptors).

(Ancila Nhamo, Camille Bourdier, décembre 2022)

The Matobo Hills in History

The human history in Zimbabwe spans more than a million years. It is divided into the Stone Age, Farming Communities period (i.e. Iron Age), and Historical Period. The Stone Age is further divided into the Earlier Stone Age (ESA), Middle Stone Age (MSA) and the Later Stone Age (LSA). Although the Matobo displays some of the earliest evidence of human history in Zimbabwe, it is poorly characterised here. The hand axes and cleavers recovered at sites (Bambata, Pomongwe, Nswatugi) have no secure contexts to enable absolute dating. Substantial information is available for the MSA and the LSA for which Matobo material has played a key role in defining the cultural sequence in Zimbabwe and parts of Botswana (Walker and Thorp, 1997; Walker, 1998; Larsson, 2001). Two successive cultural stages were defined for the MSA after Bambata Cave and Tshangula assemblages. There is some controversy over a possible last MSA stage: the Magosian.

The LSA appears a little later than in other parts of Zimbabwe and southern Africa. It is believed that the massif may not have been occupied during the Last Glacial period (25.000-15.000 BP) because of aridity, with only intermittent occupations from 15.000 BP until the environment began warming towards the end of the Pleistocene, about 13.000 BP (Walker, 1995). Several cultural stages follow until the Late Holocene, characterized by changes in the assemblages (lithics, bone equipment, personal ornaments): Maleme (13.000-11.000 BP), Pomongwe (11.000-9.400 BP) with smaller stone and bone tools, Nswatugi (9.300-4.500 BP) – previously known as the Wilton – with typical microlithic tools and elaborate ornaments with ostrich eggshell and shell beads, Amadzimba (4.500-2.000 BP), and the Ceramic LSA (2.000-300 BP) (Walker and Thorp, 1997).

The LSA also sees the development of one of the most significant cultural features of the Matobo UNESCO World Heritage Landscape: the rock paintings of humans and animals that cover walls of thousands of rock shelters, rock overhangs and boulder faces (Garlake, 1987, 1995; Mguni, 2015; Walker, 1996; Nhamo and Bourdier, 2019). The earliest rock art is thought to date from the onset of the LSA around 13.000 BP at Pomongwe Cave and Cave of Bees (Walker, 1996), although confirmation is currently underway within the MATOBART Research Program.

The Matobo UNESCO World Heritage Landscape plays a significant role in the archaeology of Farming communities in Zimbabwe and southern Africa. The site of Bambata gave its name to the pottery associated with the first pastoral/farming communities in Zimbabwe (Huffman, 2007). This evidence is taken to indicate the southwards movement of pastoral/farming populations (around 2.000 years ago), introducing a different way of life to the hunter-gatherers’ in southern Africa. Still remains a debate about the presence of such pottery in the last hunters-gatherers’ occupations prior to the arrival of pastoral/farming populations, hence questioning a local autonomous invention (Walker, 1995). It is believed that hunter-gatherer communities may have survived long into the historical times in western Zimbabwe and possibly in the Matobo (Ranger, 1999).

The Matobo has landmarks of recent historical events in the 19th century and beginning 20th century (Burrett et al., 2016; Hubbard, 2018). The Ndebele movement into the area (1832) and related conflicts brought some new archaeological signatures: A different pottery, clay grain bins, and news shrines such King Mzilikazi’s homestead (Mdhladhlandela) and grave. There are also places that define the initial colonial conduct and succeeding colonial dominance such as the famous negotiation between the colonial force (indaba) and Ndebele leaders after the rebellion of 1896. Cecil John Rhodes’s grave and the graves of some of his generals at World’s View have become one of the famous landmarks of the Matobo UNESCO World Heritage Landscape.

(Ancila Nhamo, Camille Bourdier, décembre 2022)

The Matobo Hills today

The Matobo UNESCO World Heritage Landscape lies about 35 km south of Bulawayo, the country’s second largest city, in south-western Zimbabwe. It covers an area of about 3100 km² which includes the Matobo National Park, established in 1926 as the Rhodes Matopos National Park and famous for its wilderness, communal lands, and a small part of commercial farmland. It is a rocky landscape broken by several valleys that make up the famous undulating viewscape endowed with a unique natural, cultural, and living heritage. The Hills contain a rich archaeological and historical heritage, and notably one of the highest concentrations of prehistoric hunters-gatherers’ rock paintings in Southern Africa. Some painted sites can be visited (Pomongwe, Nswatugi, White Rhino, Silozwane). A small site museum at Pomongwe Cave showcases some fascinating heritage of the hills and its people.

The Matobo is also a living heritage. It has for centuries been associated with a regional oracle of the High God/Mwari/Mlimo, whose voice is said to be heard from the rocks in this landscape. This powerful oracle links the indigenous communities from all over Zimbabwe and other parts of southern Africa to the hills with their deep caves, sacred forests, trees and pools. As such, the Matobo landscape has powerful shrines such as Njelele, Zhilo and Dula that are revered up until the present (Kumirai et al., 2013).

Matobo is also a memorial place from the colonial period, with the memorial shrine for Memorable Order of the Tin Hats which commemorates those who perished during World War I and II, and the graves of prominent colonial personalities such as Cecil John Rhodes, Leander Starr Jameson, Alan Wilson at the World’s View (Burret et al., 2016).

(Ancila Nhamo, Camille Bourdier, décembre 2022)

Publications

ERBATI, Elarbi, FAUVELLE, François-Xavier, MENSAN, Romain (dirs.), 2020, Sijilmâsa, cité islamique du Maroc médiéval. Recherches archéologiques maroco-françaises 2011-2017, VESAM, IX, Rabat, INSAP.

Bibliographie

AL-BAKRÎ, trad. de Slane, M. G., 1858, « Description de l’Afrique septentrionale », Journal Asiatique, p. 516-524.

Al-IDRÎSÎ, trad. Bresc, H. et Nef, A., 1999, La première géographie de l’Occident, Paris, Flammarion.

AUDOLLENT, Auguste, 1901, Carthage romaine (146 avant J.-C.-698 après J.-C.), Paris, A. Fontemoing.

BEN JERBANIA, Imed et alii, 2020, « Nouvelles fouilles dans le sanctuaire de Ba'l Hamon à Carthage », IX Congreso Internacional de Estudios Fenicios y Púnicos, p. 1141-1156.

CHATEAUBRIAND, François-René (de), 1811, Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem, Paris, P.-H. Krabbe.

CINTAS, Pierre, 1970-1976, Manuel d’archéologie punique, Paris, Picard.

DAVIN, Paul, 1930, « Étude sur la cadastration de la Colonia Iulia Karthago », Revue Tunisienne, p. 73-83.

DEBERGH, Jacques, 2000, « L’aurore de l’archéologie à Carthage au temps de Hamouda Bey et de Mahmoud Bey (1782-1824) : Frank, Humbert, Caronni, Gierlew, Borgia », Africa Romana, XIII, p. 457-474.

DEBERGH, Jacques, 2002, « Voici les ports », « non », Jean Humbert et la localisation des installations portuaires de Carthage », Africa Romana, XIV, p. 469-480.

DESFONTAINES, René Louiche, 1883, Fragments d’un voyage dans les régences de Tunis et d’Alger fait de 1785 à 1786, Paris, Dureau de la Malle.

DRAPPIER, Louis et MERLIN, Alfred, 1909, La nécropole punique d’Ardh el Kheraïb, Paris, Ernest Leroux.

DUVAL, Noël et LÉZINE, Alexandre, 1959 « Nécropole chrétienne et baptistère souterrain à Carthage », Cahiers Archéologiques, X, p. 71-147.

ENNABLI, Abdelmagid (dir.), 1992, Pour sauver Carthage, Exploration et conservation de la cité punique, romaine et byzantine, Paris, INAA-UNESCO.

ENNABLI, Abdelmagid, 1995, « La campagne internationale de Carthage 1972-1994 », Dossiers d’Archéologie, 200, p. 102-117.

ENNABLI, Abdelmagid, 2020, Carthage. Les travaux et les jours. Recherches et découvertes, 1831-2016, Paris, Éditions du CNRS.

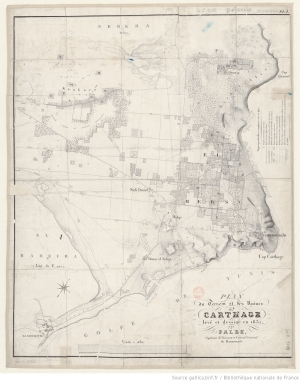

FALBE, Christian Tuxen, 1831, Plan du terrain et des ruines de Carthage levé et dessiné en 1831 par Falbe, capitaine de vaisseau et consul général de Danemark, au 1/64 000e, Paris, Imprimerie royale.

FALBE, Christian Tuxen, 1833, Recherches sur l’emplacement de Carthage suivies de plusieurs inscriptions puniques inédites, de notices historiques, géographiques, etc… avec le plan topographique du terrain et des ruines de la ville dans leur état actuel et cinq autres planches, Paris, Imprimerie royale.

GAUCKLER, Paul, 1902, « L’odéon des jeux pythiques de Carthage », RA, II, p. 387-399

GAUCKLER, Paul, 1903, « Le quartier des thermes d’Antonin et le couvent de Saint-Étienne à Carthage », BCTH, p. 410-420, pl. XXV.

GAUCKLER, Paul, 1907, « Le théâtre de Carthage », NAM, XV, p. 452-472.

GAUCKLER, Paul, 1910, Inventaire des mosaïques de la Gaule et de l’Afrique, t. 2, Afrique proconsulaire (Tunisie) (IMT), Paris, Ernest Leroux.

GAUCKLER, Paul, 1915, Nécropoles puniques à Carthage, Paris, Auguste Picard.

GOLVIN, Jean-Claude, LARONDE, André, 2001, L’Afrique antique : histoire et monuments, Paris, Tallandier.

GSELL, Stéphane, 1913-1920, Histoire ancienne de l’Afrique du Nord, t. I et II, Paris, Hachette.

LANCEL, Serge, 1992, Carthage, Paris, Fayard.

LAPEYRE, Gabriel Guillaume et PELLEGRIN, Arthur, 1942, Carthage punique (814-146 av. J.-C.), Paris, Payot.

LAPEYRE, Gabriel Guillaume et PELLEGRIN, Arthur, 1950, Carthage latine et chrétienne, Paris, Payot.

MERLIN, Alfred, 1921, « La mosaïque du seigneur Julius à Carthage », BCTH, p. 35-114

PEYSONNEL, Jean-André, 1838, Relations d’un voyage sur les côtes de Barbarie fait par ordre du Roi en 1724 et 1725, Paris, Dureau de la Malle.

PEYSONNEL, Jean-André, 2001, Voyage dans les régences de Tunis et d’Alger, Paris, Édition La Découverte.

PICARD, Gilbert-Charles, 1956, Le Monde de Carthage, Paris, Corréa.

PICARD, Gilbert-Charles et LEZINE, Alexandre, 1956, « Observations sur la ruine des thermes d’Antonin à Carthage », CRAI, p. 425-430.

Les recherches les plus récentes ou en cours

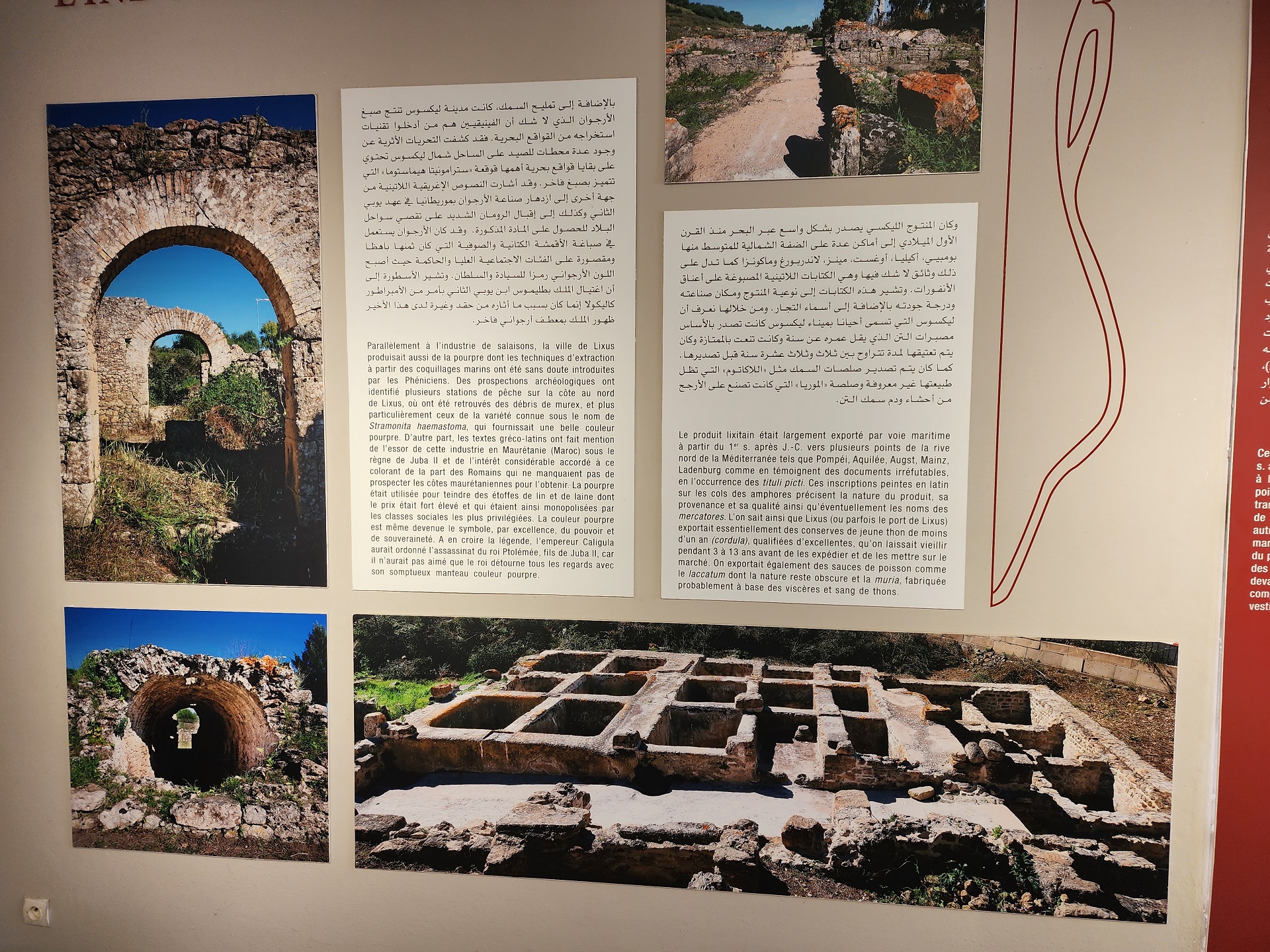

La campagne de fouilles internationales de Carthage a été une opération d’envergure entreprise, avec le soutien de l’UNESCO, entre 1972 et 1994 pour éviter qu’un site porteur d’une grande histoire disparaisse dans l’indifférence générale. Grâce à la persévérance d’équipes de fouilleurs issus de nombreux pays, d’importantes découvertes furent réalisées, d’abord pour la période romaine, en particulier la confirmation du forum au sommet de Byrsa, et pour la période punique, jusque-là méconnue. Parmi beaucoup de nouveautés, les fouilles internationales ont révélé la configuration des deux bassins portuaires, le bassin marchand et surtout le port militaire dont l’architecture et le plan ont été bien restitués. Plus au nord, c’est tout un quartier d’habitat punique qui a été révélé en bordure de mer, à l’abri d’une muraille servant de rempart maritime. Sur le versant de la colline de Byrsa, un autre quartier punique construit selon les meilleures techniques a été mis au jour. Dans la plaine littorale, des sondages profonds ont révélé les premières traces de l’occupation humaine sur le site. Tous ces vestiges ont fait l’objet de soins attentifs : consolidés et restaurés, mis en valeur, ils sont accessibles au public qui peut les visiter. Des antiquarium et des maquettes permettent de faciliter la compréhension.

Pour la période romaine, déjà illustrée par de nombreux vestiges de grands monuments tels que les thermes d’Antonin, le quartier des domus aristocratiques, l’amphithéâtre et les grands réservoirs, d’autres découvertes ont été faites, en particulier la révélation au sommet de la colline de Byrsa de l’existence du forum de la ville, un des plus vastes de l’empire romain, bien que très ruiné en raison de l’exploitation de ses matériaux : colonnes, chapiteaux qui ont été emportés. Le plan du forum a été restitué et matérialisé au sol, et une maquette en présente l’architecture, en particulier, dominant la place publique, la grande basilique civile qui fut le centre du pouvoir politique de la province d’Africa. Un grand temple s’élevait à proximité. À l’emplacement du port militaire d’époque punique s’est substitué un autre port destiné à l’expédition de l’annone, la contribution en blé produit par l’Africa à destination de la capitale de l’empire. D’autres monuments ont été dégagés ou explorés, en particulier le cirque-hippodrome, les grandes citernes de La Malga, l’édifice de la Rotonde. Le schéma urbanistique de la ville, dont la cadastration orthogonale, avait été déjà découverte, a été confirmé dans sa régularité. Le contour des remparts élevés au Ve s., à la veille de l’invasion vandale, a été retrouvé et son plan restitué. Une nouvelle nécropole païenne a livré des mausolées construits comportant des décors stuqués et deux statues funéraires en marbre blanc. Venant s’ajouter aux basiliques chrétiennes déjà fouillées au XIXe et XXe s., une nouvelle église a été découverte et soigneusement fouillée en bas de la colline de Byrsa, dans la plaine littorale. Dans ce quartier de Carthagenna, elle est proche d’une autre ayant suivie une évolution à peu près semblable, du IVe au VIIe s. À la périphérie nord-ouest de la ville, les vestiges de la basilique de Bir Ftouha ont fait l’objet d’une recherche archéologique très poussée ayant permis de mieux restituer ce monument. Une autre basilique cimetériale datant sans doute de la période vandale, située, elle, dans le quartier sud-est proche d’un endroit nommé justement Bir el Knissia (le puits de l’église), a été révélée.

La totalité du matériel archéologique découvert lors de la Campagne internationale a été documenté et est conservé dans les réserves du musée de Carthage qui présente dans quelques salles les objets et les séquences les plus remarquables. L’ancien musée Lavigerie, situé au sommet de Byrsa, a en effet été réaménagé, rénové, et une nouvelle exposition muséographique a été réalisée tenant compte de tous les apports de ces fouilles. En particulier, une galerie a été consacrée aux fouilles de la colline de Byrsa, présentant à la fois le forum romain et le quartier punique qui l’avait précédé. Aujourd’hui fermé au public, le musée de Carthage est en cours de réaménagement et devrait rouvrir ses portes en 2024.

Pendant toute la durée de la campagne, un bulletin d’information (Bulletin CEDAC) a été publié et diffusé, consignant annuellement les découvertes et les travaux effectués par les équipes internationales. Un ouvrage collectif (Ennabli, 1992) fut édité en 1992 par l’UNESCO et l’Institut d’Archéologie de Tunis, rapportant l’essentiel des travaux, accompagné d’une bibliographie exhaustive. Des ouvrages de synthèse s’ensuivirent ; citons en particulier celui de Serge Lancel (Lancel, 1992), intitulé Carthage. Un numéro spécial des Dossiers d’Archéologie (1995), ayant pour titre Tunisie, Carrefour de Civilisations, présente les principaux résultats de cette campagne et évoque les perspectives d’avenir. Outre les nombreuses monographies publiées par chacune des équipes, un bilan est donné dans Carthage : « les Travaux et les Jours » (Ennabli, 2020). Le site de Carthage apparaît aujourd’hui comme l’un des sites les plus documentés de la Méditerranée. Des recherches actuelles entretiennent cet important héritage scientifique et contribuent au renouvellement des connaissances par le recours aux méthodes et aux techniques de spécialités récentes ; c’est le cas notamment dans le secteur du tophet de Salammbô où se pratiquent désormais des études archéothanatologiques. Il est néanmoins à noter qu’en l’absence de Plan de Protection et de Mise en Valeur (pourtant prévu par le Code de Protection culturelle depuis 1994), il n’existe pas de fouilles programmées à Carthage, mais des sondages d’urgence effectués sur demande de permis de bâtir.

(Abdelmajid Ennabli, avril 2022)

Histoire de la recherche à Carthage

Le site fut visité occasionnellement par des voyageurs européens qui décrivirent les ruines en évoquant son passé. Citons en particulier Peysonnel en 1723 et Chateaubriand (1811) en 1807 qui parcourut le site accompagné de l’ingénieur hollandais E. Humbert (Debberg, 2000, 2002 ; Catalog, 2017) en charge de la construction du port de La Goulette et grand connaisseur des vestiges carthaginois. En 1830, Falbe, consul danois, dresse le premier plan du site (Falbe 1831, 1833) et de l’ensemble de la presqu’île, tels qu’ils étaient visibles à l’époque. Les Pères blancs de Carthage, directeurs successifs du musée Lavigerie : Alfred-Louis Delattre (1875-1932), Georges Lapeyre (1932-1947), Jean Ferron (1948-1964) d’un côté, les directeurs du service des Antiquités : Paul Gauckler (1892-1905), Alfred Merlin (1905-1920), Louis Poinssot (1920-1940), Gilbert-Charles Picard (1942-1955) de l’autre, se sont partagé les fouilles et les recherches. Ils ont bénéficié de la participation active de Pierre Cintas (Cintas, 1970-1976) à partir de 1946, d’Alexandre Lézine, architecte, ainsi que de quelques archéologues bénévoles tels que Louis Carton et Charles Saumagne. Les collections d’objets découverts par Delattre ont été déposés au musée Lavigerie à Byrsa. Les collections mises au jour par les directeurs des Antiquités, au musée du Bardo.

Delattre a cherché et fouillé les basiliques chrétiennes : Damous el Karita, Saint-Cyprien, Basilica Majorum, Bir Ftouha, Bir el Knissia. Il a effectué quelques dégagements dans le théâtre, l’amphithéâtre et la villa dite de Scorpianus. Mais surtout, il a fouillé les nécropoles païennes de La Malga et celles, puniques, de Douïmes, de l’odéon et du théâtre, en particulier la nécropole des Rabs à Sainte-Monique. Les découvertes réalisées par Delattre ont été publiées régulièrement dans la revue Cosmos et dans celle des Missions Catholiques, et aussi dans les CRAI, les MSAF. Lapeyre a fouillé longuement le tophet qui venait d’être découvert, accumulant les stèles et les urnes dégagées au musée Lavigerie, sans publier ces découvertes de manière exhaustive. Ferron s’est d’abord consacré aux dégagements du quartier situé sur le flanc sud de Byrsa. Il en a publié les résultats dans la revue Cahiers de Byrsa, vol. I et V. Pour ce qui est du service des Antiquités, Gauckler (Gauckler, 1896-1903, 1902,1903, 1907, 1910, 1915) est celui qui s’est le plus investi dans les fouilles à Carthage, tant pour la période punique que pour la période romaine : nécropoles de Dermech et odéon-théâtre. Les fouilles dans le secteur de Dermech ont mis au jour plusieurs domus comportant des mosaïques ainsi que dans le secteur dit des « villas romaines » proche de l’odéon et du théâtre, eux aussi dégagés, et sur le plateau de Borj Jedid, des domus avec mosaïques tardives. Alfred Merlin, accompagné de Louis Drappier (1909), a fouillé et publié la nécropole punique d’Ardh el Kheraïb, sise à Borj Jedid, et réalisé la publication de la mosaïque « du Seigneur Julius » (Merlin, 1921), mais sans fournir le contexte archéologique ; il a aussi chargé une troupe de soldats de fouiller le port militaire. Poinssot s’est occupé de la restauration de l’« Édifice à colonnes » et de quelques domus sur le plateau de l’odéon. Picard a procédé au dégagement des thermes d’Antonin avec une main-d’œuvre abondante (1944-1954). Mais c’est Lézine qui en a fait l’étude exhaustive (Picard, Lézine, 1956). Il a confié à Cintas la fouille d’un secteur du tophet. Celui-ci a publié ses recherches dans les Manuel d’Archéologie Punique (Cintas, 1970-1976) en deux tomes. Ajoutons les sondages et recherches de Charles Saumagne qui découvrit la cadastration urbaine (Saumagne, 1930). Et concluons avec une fouille d’urgence pratiquée dans le chantier de construction du lycée de Carthage dessiné par Jacques Marmey, qui s’est édifié sur un terrain destiné à l’origine à être une partie du parc de Carthage. Noël Duval et Alexandre Lézine (Duval, Lézine, 1959) ont donné le résultat de leurs recherches dans les Cahiers archéologiques 1959. Comme ouvrages de synthèse, il convient de signaler le livre d’Auguste Audollent sur Carthage romaine (Audollent, 1901), étude fondamentale mais publiée en 1901, c’est-à-dire avant les découvertes ultérieures, et celui de Stéphane Gsell (Gsell, 1913-1920) en 8 volumes Histoire ancienne de l’Afrique du Nord dont les quatre premiers, parus entre 1913 et 1928, sont consacrés à Carthage. Ajoutons les deux ouvrages de Gabriel Guillaume Lapeyre et Arthur Pellegrin (Lapeyre, Pellegrin, 1942, 1950), le premier sur la Carthage punique, paru en 1942, et celui sur la Carthage romaine paru en 1950. Gilbert-Charles Picard a édité un ouvrage général intitulé Le monde de Carthage, ouvrage illustré de photographies mêlant les deux périodes (Picard, 1956). En somme, il n’y a jamais eu sous le protectorat de programme de fouille méthodique, mais seulement des découvertes locales et fortuites, la Carthage punique, en dehors de ses nécropoles, restant alors introuvable.

(Abdelmajid Ennabli, avril 2022)