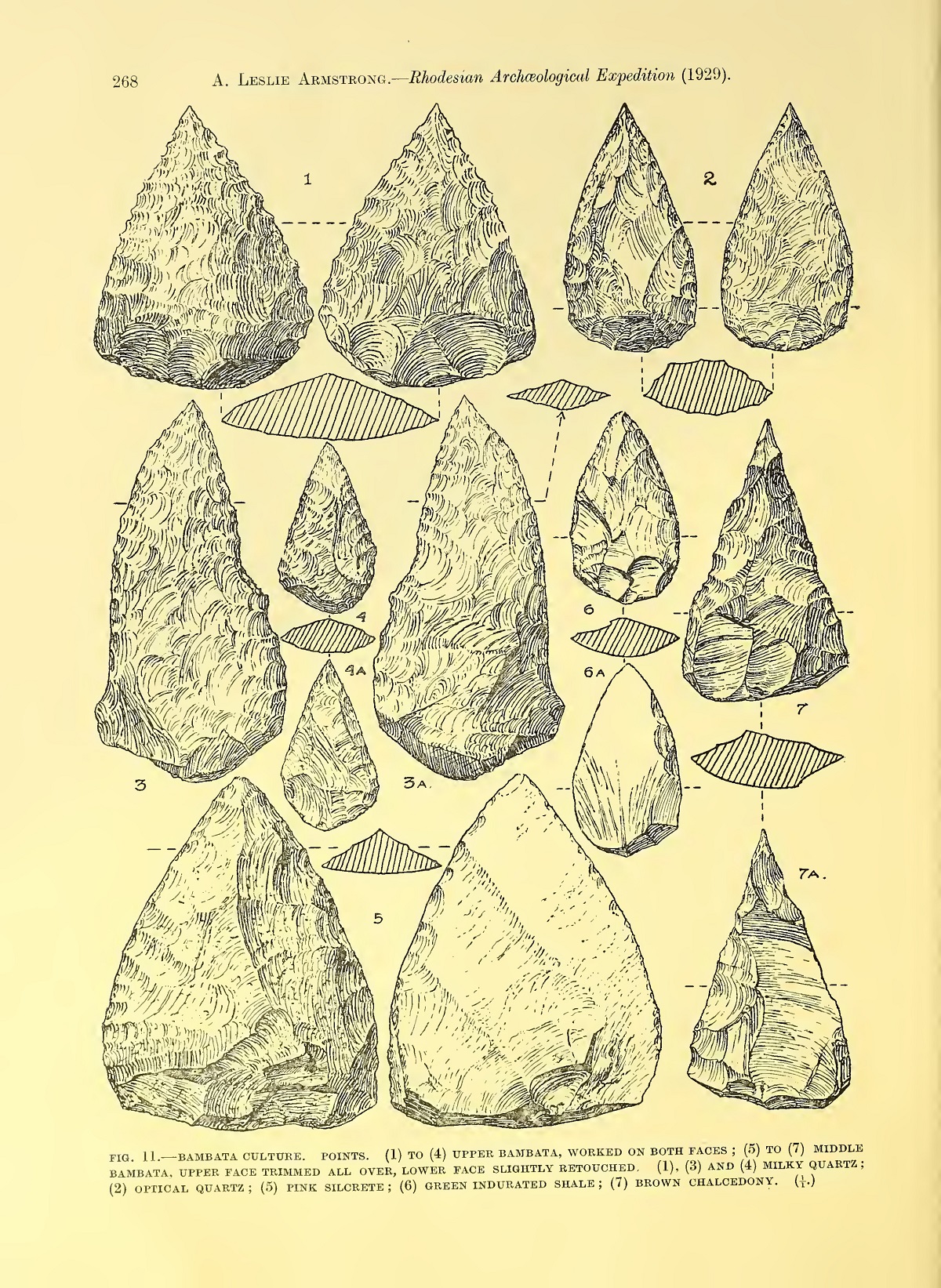

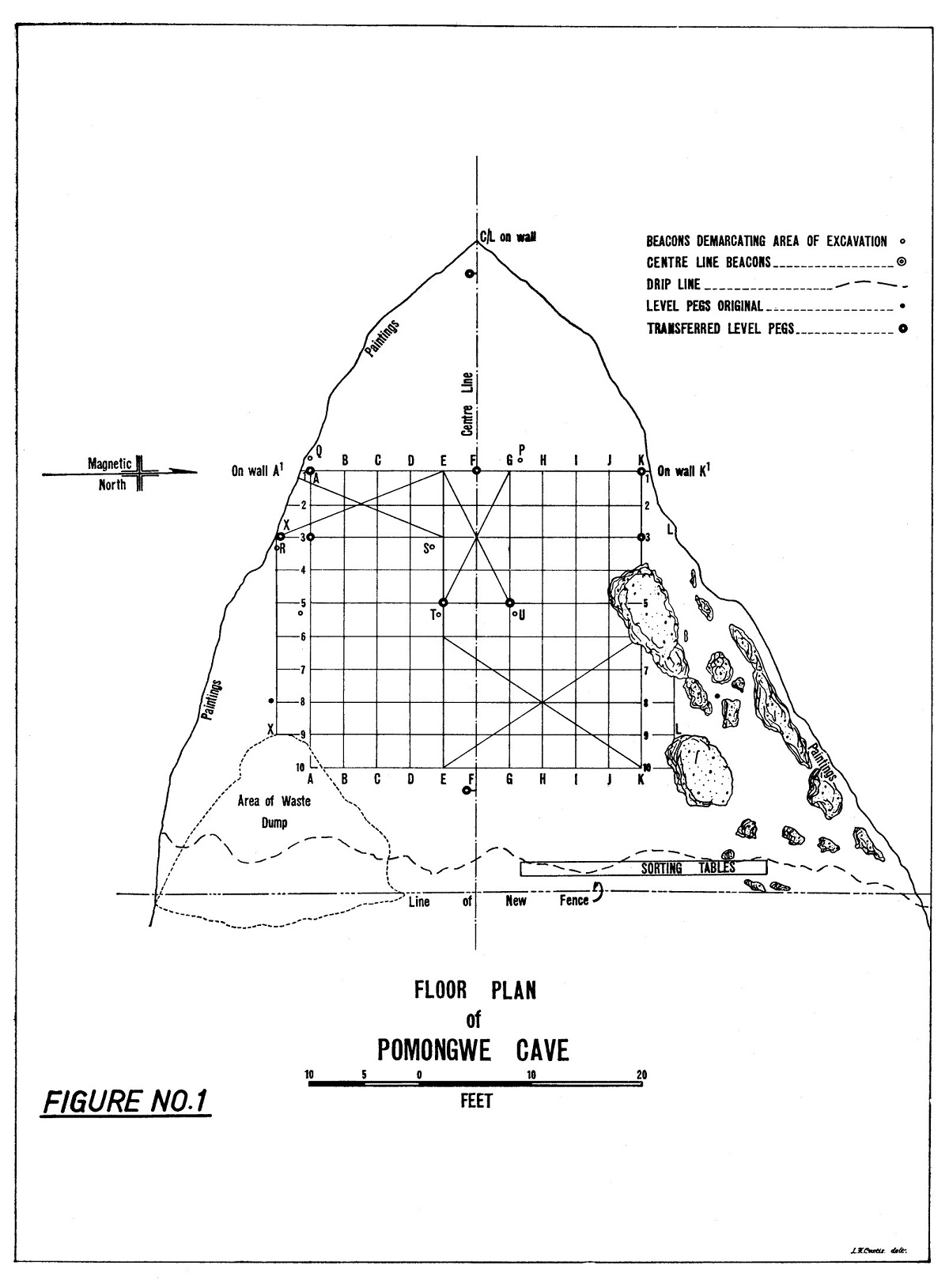

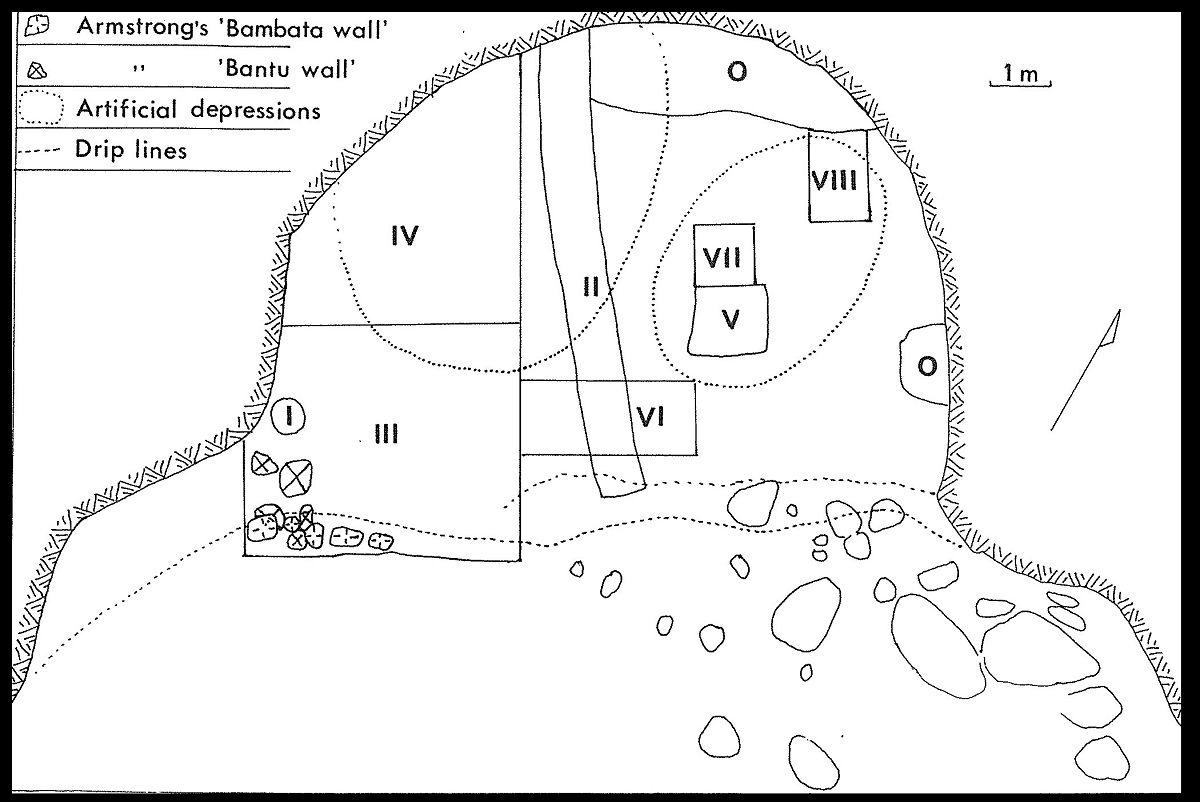

The human history in Zimbabwe spans more than a million years. It is divided into the Stone Age, Farming Communities period (i.e. Iron Age), and Historical Period. The Stone Age is further divided into the Earlier Stone Age (ESA), Middle Stone Age (MSA) and the Later Stone Age (LSA). Although the Matobo displays some of the earliest evidence of human history in Zimbabwe, it is poorly characterised here. The hand axes and cleavers recovered at sites (Bambata, Pomongwe, Nswatugi) have no secure contexts to enable absolute dating. Substantial information is available for the MSA and the LSA for which Matobo material has played a key role in defining the cultural sequence in Zimbabwe and parts of Botswana (Walker and Thorp, 1997; Walker, 1998; Larsson, 2001). Two successive cultural stages were defined for the MSA after Bambata Cave and Tshangula assemblages. There is some controversy over a possible last MSA stage: the Magosian.

The LSA appears a little later than in other parts of Zimbabwe and southern Africa. It is believed that the massif may not have been occupied during the Last Glacial period (25.000-15.000 BP) because of aridity, with only intermittent occupations from 15.000 BP until the environment began warming towards the end of the Pleistocene, about 13.000 BP (Walker, 1995). Several cultural stages follow until the Late Holocene, characterized by changes in the assemblages (lithics, bone equipment, personal ornaments): Maleme (13.000-11.000 BP), Pomongwe (11.000-9.400 BP) with smaller stone and bone tools, Nswatugi (9.300-4.500 BP) – previously known as the Wilton – with typical microlithic tools and elaborate ornaments with ostrich eggshell and shell beads, Amadzimba (4.500-2.000 BP), and the Ceramic LSA (2.000-300 BP) (Walker and Thorp, 1997).

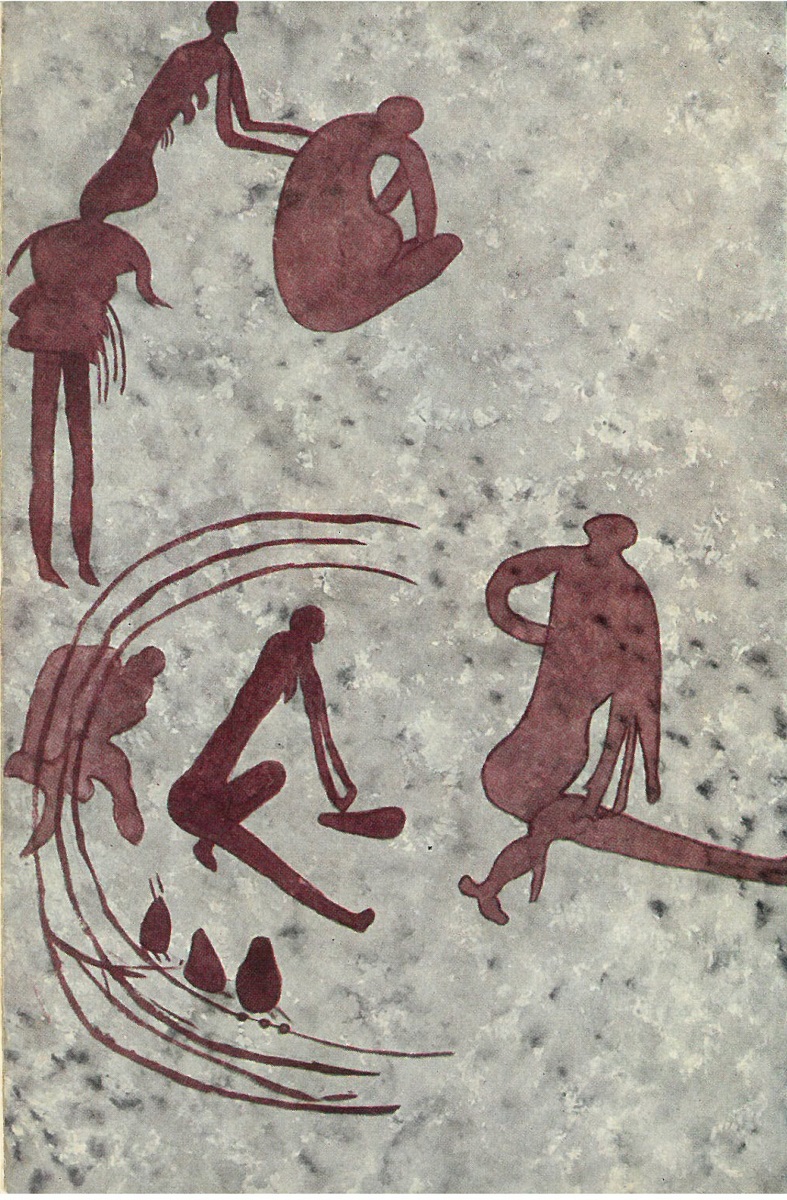

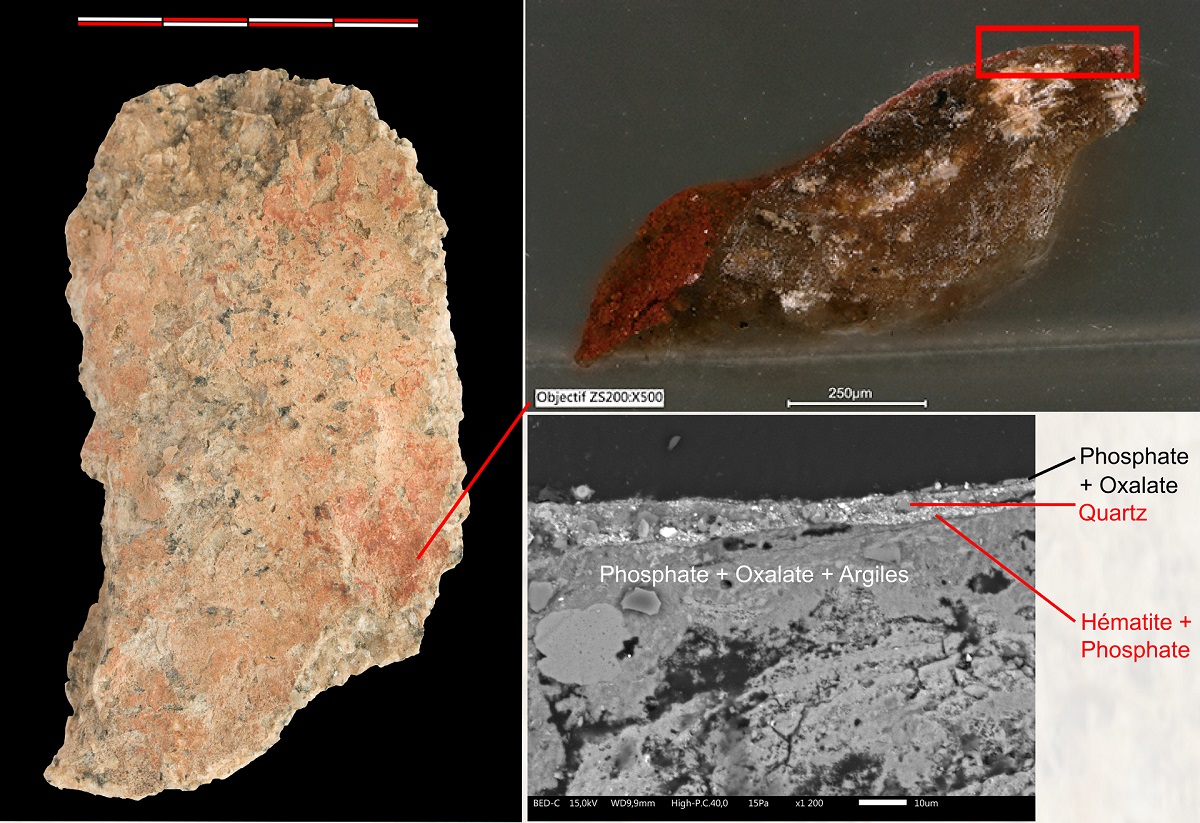

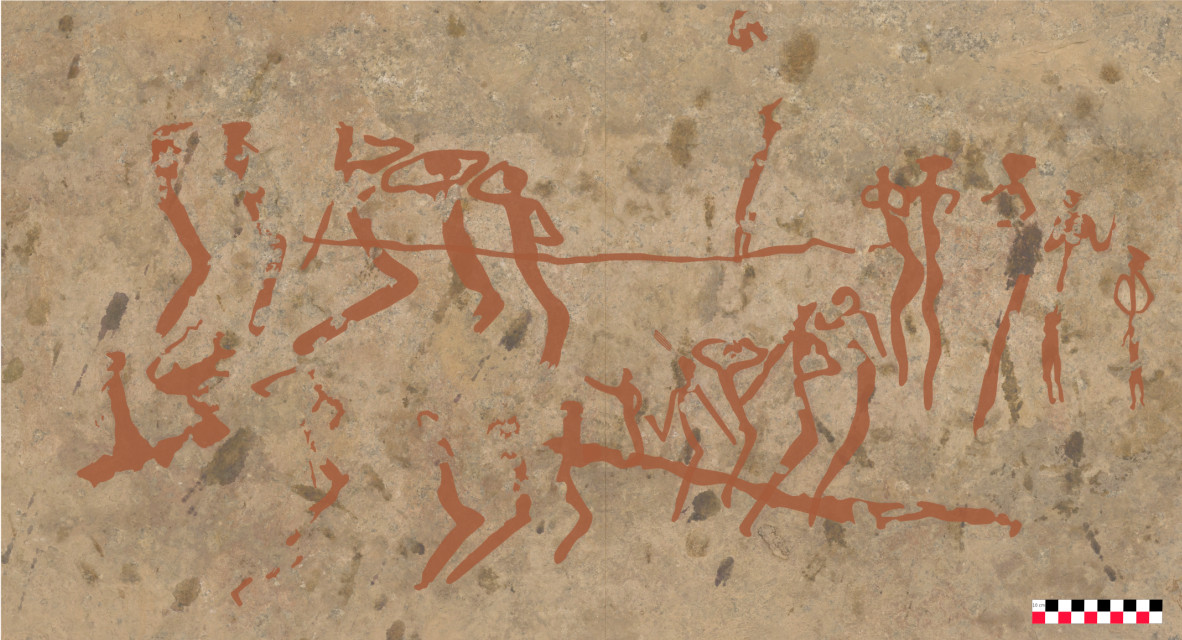

The LSA also sees the development of one of the most significant cultural features of the Matobo UNESCO World Heritage Landscape: the rock paintings of humans and animals that cover walls of thousands of rock shelters, rock overhangs and boulder faces (Garlake, 1987, 1995; Mguni, 2015; Walker, 1996; Nhamo and Bourdier, 2019). The earliest rock art is thought to date from the onset of the LSA around 13.000 BP at Pomongwe Cave and Cave of Bees (Walker, 1996), although confirmation is currently underway within the MATOBART Research Program.

The Matobo UNESCO World Heritage Landscape plays a significant role in the archaeology of Farming communities in Zimbabwe and southern Africa. The site of Bambata gave its name to the pottery associated with the first pastoral/farming communities in Zimbabwe (Huffman, 2007). This evidence is taken to indicate the southwards movement of pastoral/farming populations (around 2.000 years ago), introducing a different way of life to the hunter-gatherers’ in southern Africa. Still remains a debate about the presence of such pottery in the last hunters-gatherers’ occupations prior to the arrival of pastoral/farming populations, hence questioning a local autonomous invention (Walker, 1995). It is believed that hunter-gatherer communities may have survived long into the historical times in western Zimbabwe and possibly in the Matobo (Ranger, 1999).

The Matobo has landmarks of recent historical events in the 19th century and beginning 20th century (Burrett et al., 2016; Hubbard, 2018). The Ndebele movement into the area (1832) and related conflicts brought some new archaeological signatures: A different pottery, clay grain bins, and news shrines such King Mzilikazi’s homestead (Mdhladhlandela) and grave. There are also places that define the initial colonial conduct and succeeding colonial dominance such as the famous negotiation between the colonial force (indaba) and Ndebele leaders after the rebellion of 1896. Cecil John Rhodes’s grave and the graves of some of his generals at World’s View have become one of the famous landmarks of the Matobo UNESCO World Heritage Landscape.

(Ancila Nhamo, Camille Bourdier, décembre 2022)