Matobo has a long history of archaeological research, since the beginning of the 20th century when the first European archaeologists begun to work in the region, and especially the rock art (N. Jones, M.C. Burkitt, L.A. Armstrong, C. Cooke). In other regions, traditional laws within local communities protected heritage sites, including rock art, for centuries (Makuvaza, 2014). Such a system must have existed in Matobo as well, which would explains the high number and exceptional preservation of the rock art sites at present (Ranger, 1999; Hubbard, 2018).

Until the 1980s, archaeological research was driven by the building of the regional Stone Age chrono-cultural sequence and rock art chrono-stylistic sequence. In such purpose the two first generations of prehistorians made attempts to correlate ground occupations and rock paintings. Several rock art sites were then excavated from the first half of the 20th century, notably Bambata (Arnold and Jones, 1919; Armstrong, 1931), Nswatugi (Jones, 1926, 1933), Amadzimba (Cooke and Robinson, 1954), Pomongwe and Tshangula (Cooke, 1963a). In the 1970s, a few sites were re-investigated by Nick Walker who also excavated a handful of new ones with a special focus on the Later Stone Age (LSA) sequence of occupation, from the Late Pleistocene to the Late Holocene (Walker, 1995). Apart from the redefinition of the chrono-cultural sequence, he specifically addressed the subsistence strategies, and adopted a paleo-social perspective with a multi-proxies approach (ecofacts, artefacts, sites distribution and features, rock art). In relation to climatic and environmental factors, he stated a model of socio-cultural dynamics in the longue durée, including elements of demography, settlement pattern, and social structuring.

With deep stratigraphic sequences, and extremely good organic preservation, the Matoban sites have proven to be key for the Stone Age cultural sequence of the whole southern Africa, from the Earlier Stone Age (Bambata, Pomongwe) in the Mid-Pleistocene up to the end of the LSA (Walker and Thorp, 1997). Amongst them, Bambata and Tshangula remain preeminent for the transition from MSA (Middle Stone Age) to the LSA regarding the issue of the cultural dynamics between these two phases (filiation vs break – Larsson, 2001; Walker, 1998). In Bambata again, the presence of pottery remains in the most recent occupations attributed to foragers’ populations put to question the effective influence of the first pastoral populations’ arrival (cultural borrowing vs local autonomous invention – Walker, 1995; Huffman, 2007).

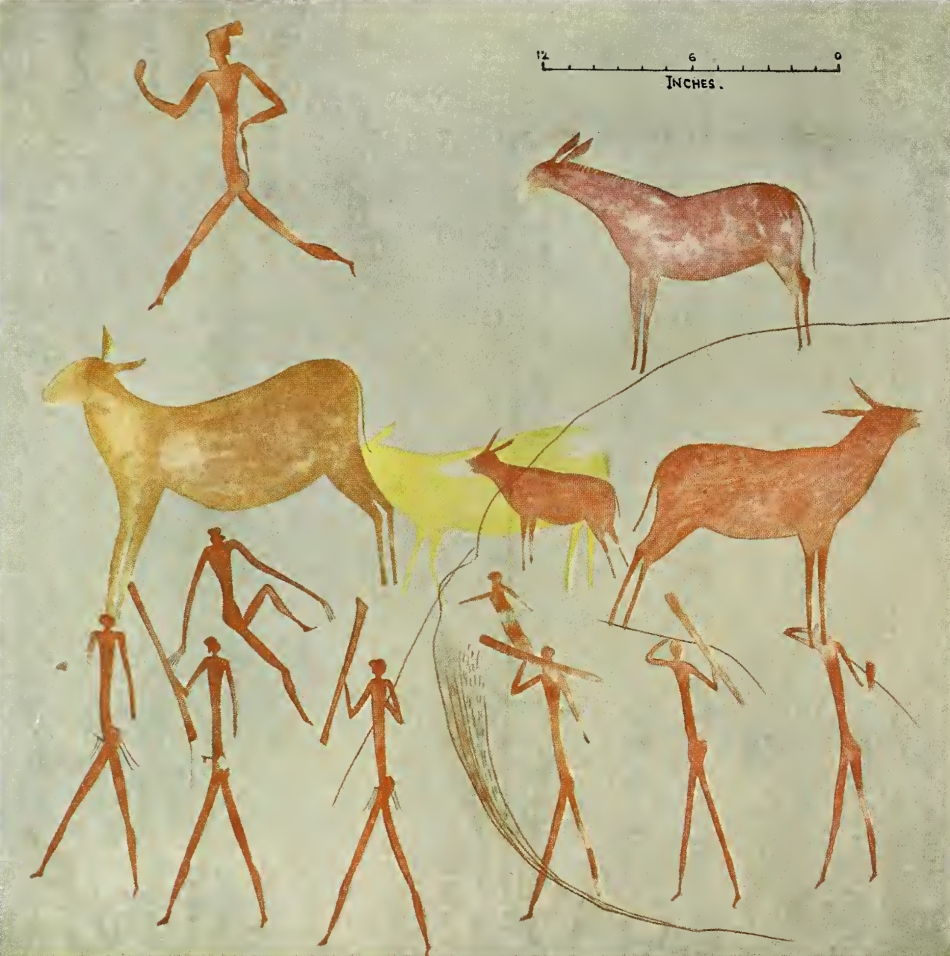

In parallel, a regional chrono-stylistic sequence of rock art was built by C. Cooke, with six styles: 4 attributed to the LSA foragers, and 2 to the Iron Age farmers (Cooke, 1963b). The LSA rock art sequence is based on a linear progressive complexification of techniques and forms, from plain monochromes to differentiated outlines and infills, fine outline drawings, and finally polychromes. This stylistic sequence has been strongly criticized for lack of objectivity and consistency in the use of analytical attributes. Walker complemented it with some radiocarbon dates obtained from the archaeological layers with material relating to the paintings (Walker, 1995, 1996). He assumed a beginning around 13.000-12.000 BP at Pomongwe and Cave of Bees which would make Matobo one of the oldest rock art testimonies, back to the Late Pleistocene (Nhamo and Bourdier, 2019).

Since the 1980s, archaeological research in Matobo has drastically reduced and focused on rock art only, with an emphasis on the meanings. Based on the exceptional ethnographic documentation from recent San populations in South Africa, this iconography was mainly considered as the expression of foragers’ spirituality – magical potencies embodied in animals, beings from the spiritual world, mythical characters – and ritual activities (Garlake, 1987; Mguni, 2015). For some scholars, it addresses a wider range of social symbolism: Gender, affiliations, and social networks identification (Garlake, 1995; Walker, 1995; Nhamo, 2013). Still none of these interpretative theories can explain all the motifs and compositions found in Matobo rock art so far.

(Camille Bourdier, Ancila Nhamo, décembre 2022)